By Christine Mai-Duc | Los Angeles Times

None of the companies that have collected royalties on the “Happy Birthday” song for the past 80 years held a valid copyright claim to one of the most popular songs in history, a federal judge in Los Angeles ruled on Tuesday.

None of the companies that have collected royalties on the “Happy Birthday” song for the past 80 years held a valid copyright claim to one of the most popular songs in history, a federal judge in Los Angeles ruled on Tuesday.

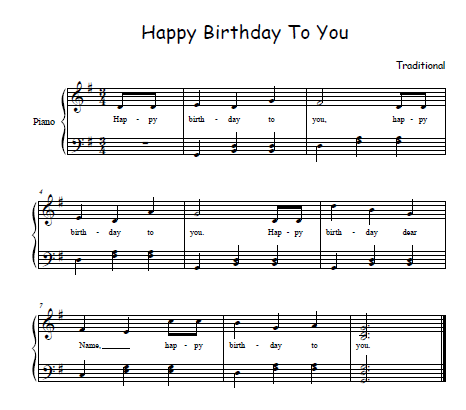

In a stunning reversal of decades of copyright claims, the judge ruled that Warner/Chappell never had the right to charge for the use of the “Happy Birthday To You” song. Warner had been enforcing a copyright since 1988, when it bought Birch Tree Group, the successor to Clayton F. Summy Co., which claimed the original disputed copyright.

Judge George H. King ruled that a copyright filed by the Summy Co. in 1935 granted only the rights to specific piano arrangements of the music, not the actual song.

“‘Happy Birthday’ is finally free after 80 years,” said Randall Newman, an attorney for the plaintiffs in the suit, which included a group of filmmakers who are producing a documentary about the song. “Finally, the charade is over. It’s unbelievable.”

A spokesman for Warner/Chappell, the publishing arm of Warner Music, said, “We are looking at the court’s lengthy opinion and considering our options.”

The plaintiffs’ attorneys had characterized the years-long legal fight as a David vs. Goliath battle that pitted independent filmmakers against a large corporation collecting profits on a song whose authors had long since died.

Rose Law Group Litigation Attorney Logan Elia commented:

“I cannot speak to the merits of this decision. I am certain this issue was the subject of very detailed briefing and I have to assume that the judge ruled correctly. Regardless, the case highlights a need to significantly reconsider intellectual property law. We take for granted that the law should allow us to own an idea. This encourages innovation and implementation by rewarding good ideas moved to market. But it is a lot less obvious why certain ideas –ones that get patented – should be protected for 17 years, while other ideas – ones that get copyrighted – should be protected more than five times longer. In modern times, it seems the rule should be reversed. With the Internet, anyone can publish copyright-type ideas worldwide with very little cost. We should question how much intellectual property protection is really necessary to incentivize new ideas. I would argue that some robust protection remains necessary to incentivize costly productions, like blockbuster movies. But, for music, I think very little protection is necessary. I predict that the world would remain a very musical place even if the term of copyright on music were significantly reduced. If we do lose certain music made by pop bands carefully orchestrated by focus groups, I am snobbishly willing to pay that price.”