By Bill Coates | PinalCentral

Writing on a computer isn’t just writing. It’s word processing. Working at newspapers, I’ve processed a lot of words since 1979.

Reporters still have to report and write stories that engage and inform. But self-editing is a lot easier on computer. For example, I tweaked this very sentence with a few taps of the keypad. It first read: “Write good on computer. But dog still bark. Hard to think. Oh, look, leftover cashew on floor. Darn. Dog eat first.”

I was nearly 30 before my first go at word processing. Before then, I processed words on a typewriter.

I learned to type in seventh grade. It was a required course at the Bellevue, Nebraska, Junior High School. It’s probably called a middle school now. I wasn’t going to win any typing awards, but I got the basics. I can still picture the quick fox jumping over that lazy dog.

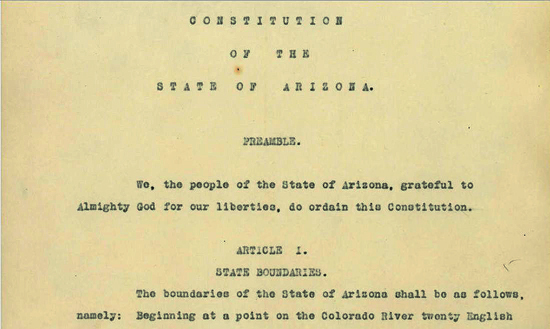

Arizona’s own Constitution is mute on the fox and the dog. But it was written in 1910 by somebody who knew the drill. The original document isn’t fancy calligraphy on parchment. It’s typewritten.

It was the first state constitution written on a typewriter. It went into effect 106 years ago Wednesday.

I had a chance to see it when I wrote for Arizona Capitol Times in the 1990s and later. Other reporters there covered matters of importance. Bills under consideration. The governor’s latest policy initiatives. And lots of stuff about the budget.

I preferred to dig around the basement. And the nooks and crannies where documents like the state Constitution were hidden away.

It’s not really kept in a nook anymore. It’s in a special climate-controlled room in the Polly Rosenbaum Archives and History Building. It opened in early 2009.

Before that, the Constitution was housed in the old state archives, between the Capitol Museum and Executive Tower. It was probably kept in a special room there, too — likely not crammed in with old city directories.

I was told there were two copies. I guess both can claim to be original.

At first glance, they don’t impress. You could mistake either one for an old high school term paper. The U.S. Constitution, on the other hand, looks the part. It’s what constitutions are supposed to look like. We’ve all seen copies of the original. “We the People …” just jumps right out at you. Large bold flourishes, followed by a schoolteacher’s dream of perfect cursive.

I suppose it’s ironic. Kids have to learn cursive in the state with the first typewritten constitution.

But it was something of an achievement. This wasn’t done on an IBM Selectric. It was 1910, after all. Typists had to bang keys like they meant it. Delegates at the constitutional convention picked 10 to do the job. I got this from the convention minutes, courtesy of the Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records.

Tag team typists.

Of course, the contents matter more than looks. And there’s nothing like going back to the source, as lawmakers did during the impeachment trial of Gov. Evan Mecham. They huddled around the original typewritten document. They wanted to see firsthand what the Constitution said about … well, that I don’t know.

Apparently, it said enough. Mecham was sent packing.

The Capitol Museum director who told me the story wanted it kept hush-hush. Or least I didn’t hear it from him. I’m not sure why. He’s since retired.

Alaska was next in line for statehood. It followed Arizona by 47 years. It did not have a typed constitution. Here’s what I learned from the Alaska State Library, which emailed a brief history. Alaska’s constitution was typeset by the publisher of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. A hundred copies were run off a corrected galley proof. Sixty were signed by delegates of the constitutional convention. I guess they’re all official.

They have a fancy old-timey font for the title page. Like some newspaper mastheads, not surprisingly. For Arizona’s title page, the typist just hit all-caps.

The next likely state is Puerto Rico. I won’t hold my breath. But when and if that happens, the Puerto Rico state constitution might end up in the cloud. You’d find it on iTunes.

In my journalism classes of the last century, a cloud was just a fluffy thing in the sky. We didn’t have computers or word processors. We typed out make-believe stories on old manual clunkers. It was good practice.

Later, at newspapers, I wrote on word processors. The future had arrived. Words appeared like magic behind the little green cursor. Move the cursor backward and they simply disappeared. The slate was clean. You could make new and better words.

There was a downside. Nobody at a typewriter ever saw all their words disappear at once. It happened with word processors and, later, computers. You’d spent hours on a story. And hours on a news story is a lifetime. Then the overhead lights would flicker. The screen would go blank. All those words you spent hours on were gone. And they weren’t coming back.

Around the newsroom, you’d realize you weren’t alone. Reporters and editors would revert to the tradition of the spoken word. Best to cover your ears.