Spotlight: Environmental defense fund report highlights strategies from Phoenix and elsewhere for managing demands on groundwater

s California embarks on its unprecedented mission to harness groundwater pumping, the Arizona desert may provide one guide that local managers can look to as they seek to arrest years of overdraft. Groundwater is stressed by a demand that often outpaces natural and artificial recharge. In California, awareness of groundwater’s importance resulted in the landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014 that aims to have the most severely depleted basins in a state of balance in about 20 years.

s California embarks on its unprecedented mission to harness groundwater pumping, the Arizona desert may provide one guide that local managers can look to as they seek to arrest years of overdraft. Groundwater is stressed by a demand that often outpaces natural and artificial recharge. In California, awareness of groundwater’s importance resulted in the landmark Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014 that aims to have the most severely depleted basins in a state of balance in about 20 years.

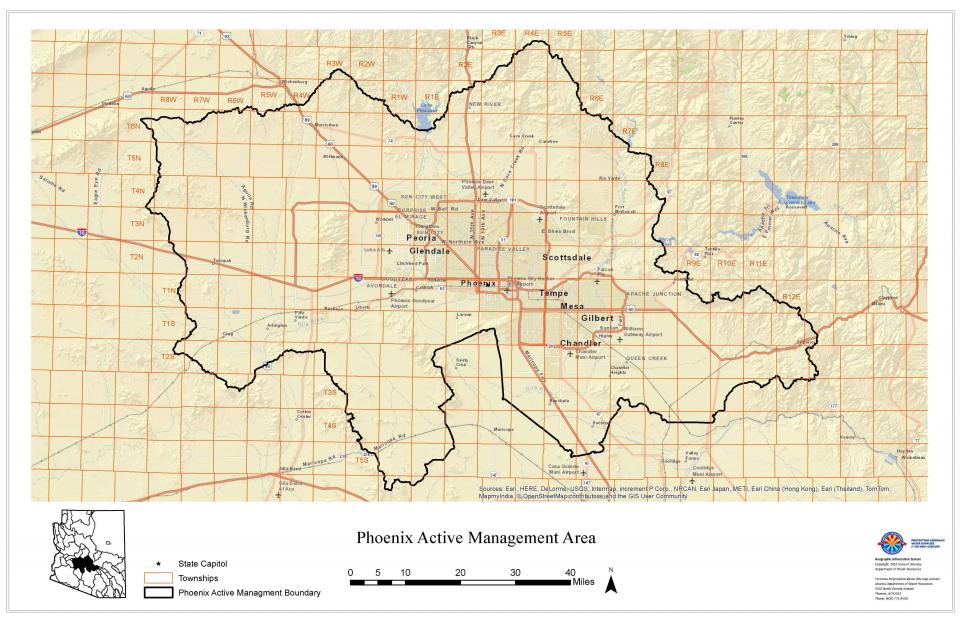

Earlier this year, the Environmental Defense Fund detailed how nine groundwater basins in six states west of the Mississippi River have confronted the need to rebalance depleted aquifers and establish successful future management. Among the areas spotlighted was the Phoenix Active Management Area (AMA), the 5,646 square-mile part of the state covered by large urban centers and tracts of farmland.

“I definitely think you can consider this a success in that they significantly halted declining groundwater levels, even given that their population has greatly increased.”

~Christina Babbitt, senior manager of EDF’s California Groundwater Program.

Groundwater is a crucial part of the water supply in the semiarid Colorado River Basin. While the river and its twin storage anchors Lake Powell and Lake Mead get much of the attention, without groundwater, large parts of the urban and agricultural landscape would not exist.

The EDF report lauds the Phoenix AMA for making “significant progress” toward reaching, by 2025, safe yield – the long-term balance between annual groundwater withdrawals and recharge — despite a population base that has tripled since 1980.

“The combination of groundwater controls and the availability of a replacement supply created an environment that was remarkably successful in shifting water use over time away from unsustainable groundwater pumping,” said the report, The Future of Groundwater in California: Lessons in Sustainable Management from Across the West.

#Read more about other examples of successful groundwater management programs highlighted in the Environmental Defense Fund’s report.

Launched through Arizona’s landmark Groundwater Management Code of 1980, the aquifer underlying the AMA “has improved significantly” through a combination of regulatory and incentive-based tools, according to EDF. Among the tools: metering of wells, a ban on new irrigated agriculture, a transfer system for groundwater rights, managed aquifer recharge and a 100-year assured water supply requirement.

“I definitely think you can consider this a success in that they significantly halted declining groundwater levels, even given that their population has greatly increased,” said Christina Babbitt, senior manager of EDF’s California Groundwater Program. “It’s important for them moving forward to continue to evaluate the tools and strategies they used to achieve that goal.”

Babbitt said Phoenix was spotlighted because of the many challenges facing the region, such as lowering groundwater levels, degraded groundwater quality and subsidence. The AMA uses several tools to watch over groundwater levels.“I think some of the things that stand out for them is their ability to offer these different regulatory approaches and give folks the opportunity to choose which best management practices they want to use,” said Babbitt. “That works to the local control nature of things.”

That “ramp-down” approach is a template for successful groundwater management, she said.

“It’s not like the hammer is coming down full-force at once,” she said. “You see how a few [best management practices] work, whether you are meeting goals and what else you might need to do over time. There are economic implications of groundwater management and recognizing what that means is important in working with people to collectively accomplish goals that are going to have better outcomes over the long run.”

The report said most effective groundwater management programs include trust, community involvement, accurate data, a portfolio of approaches and performance metrics. Reaching safe yield – defined as when total annual basin extraction does not exceed recharge – at a basin-wide level “may overlook the localized impacts of pumping,” the report said.

“Described as the ‘Swiss cheese’ effect in the aquifer … recharging in the same areas that have significant pumping depressions could help mitigate this effect,” the report said.

Dave White, a professor in the School of Community Resources and Development at Arizona State University, said the Phoenix AMA’s experience should be a lesson for the California agencies implementing SGMA.

“You need to take into account and pay close attention to the localized effects of groundwater depletion because you can see results at one scale that look good and are compliant with the law and seem to be in the right direction, but if you look smaller scale, you can see significant problems that could impact communities and agricultural users very significantly,” he said.

Nonetheless, White believes the Phoenix AMA is trending toward reaching groundwater sustainability, a tribute to the actions of past policymakers in Arizona.

“The groundwater management act that we passed in 1980 was then one of the most progressive pieces of water legislation in the U.S. and in fact if that same law was passed today somewhere else it would still be one of the most progressive pieces of legislation.”

~Dave White, professor, School of Community Resources and Development, Arizona State University.

“The groundwater management act that we passed in 1980 was then one of the most progressive pieces of water legislation in the U.S. and in fact if that same law was passed today somewhere else it would still be one of the most progressive pieces of legislation,” he said.

While Arizona’s use of Colorado River water for groundwater recharge has been effective in constructing a strong buffer, the projected reduction in river flows that climate scientists attribute to warmer basin temperatures must be kept in perspective, he said.

“As we look to the future and the probability of a shortage declaration on the Colorado River, we will lose that ability to do some of that recharge and so the lower basin states need to be very proactive in coordination … to come up with strategies to be able to maintain the water in the reservoirs to stave off the shortage declaration.”

Jeff Tannler, area director with the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said in time there will be less excess water available to agricultural users, but that “doesn’t mean that water just disappears.” Instead, it is reallocated to other users, including Native American tribes who may be interested in leasing some of that water in the future, he said.

In other cases, cities and municipalities with unused allocations of Colorado River water may choose to store the water in aquifers and provide water to agricultural users in exchange for credit that the cities can pump sometime in the future.

Here’s how others have addressed groundwater demands

The Environmental Defense Fund highlighted nine areas from Texas to Oregon that are working to address demands on groundwater, including the Phoenix Active Management Area. Here are the other eight, which employ a variety of tools, including groundwater recharge programs, pumping fees and mitigation programs.

Verde River Exchange (Arizona) — The exchange, administered by local nonprofit Friends of Verde River Greenway, is a voluntary groundwater mitigation pilot-program. The Exchange creates credits by incentivizing Verde Valley water users to voluntarily reduce their water usage. These credits can then be purchased by other Verde Valley water users seeking to reduce their water footprint and the impacts of their groundwater use.

Kings Basin (California) — The Kings River Conservation District assists growers in irrigation system reviews and water use efficiency, and also uses dedicated recharge facilities and on-farm recharge to make use of floodwater. Recharge programs in the district have the capacity to recharge over 100,000 acre-feet annually and have helped reduce rates of groundwater level declines.

Orange County Water District (California) — With no regulatory authority to control groundwater pumping, the district employs a pricing mechanism as an incentive for water retailers to purchase imported water rather than pumping groundwater. The district’s innovative pricing scheme — in combination with basin recharge, seawater barriers, water recycling, and education and outreach initiatives — exemplifies a portfolio of approaches that work together to promote cost efficiency, improved water quality and enhanced basin sustainability.

Rio Grande Water Conservation District (Subdistrict No. 1) (Colorado) — The Subdistrict places a fee on groundwater pumping to encourage irrigators to improve on-farm efficiency, switch to less water-intensive crops, and take advantage of a federal fallowing program that pays agricultural producers to take their land out of production permanently or for a certain period of time.

Upper Republican Natural Resources District (Nebraska) — Serving an agricultural basin, the district uses multiple tools to mitigate groundwater declines and satisfy requirements of an interstate compact with Colorado and Kansas pertaining to surface water flows. Examples include a moratorium on drilling new wells, a well permitting system, “land occupation” taxes, a strict cap on groundwater pumping with both formal and informal water markets, and stream augmentation projects.

Deschutes River Basin (Oregon) — The Deschutes Groundwater Mitigation Bank purchases existing surface water rights and sells corresponding mitigation credits to new groundwater pumpers. These mitigation credits have helped to preserve streamflow while allowing the approval of new groundwater permits in the basin.

Edwards Aquifer Authority (Texas) — The authority, which has a mix of agricultural and urban water users, has an aggregate cap on groundwater pumping, with tradable permits to limit groundwater withdrawal.

Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (Texas) — The district uses fees and educational programs to encourage use of surface water in lieu of groundwater. Groundwater usage is limited to a percentage of the user’s total water demand, and the user is subject to fees when that percentage is exceeded.