By Paul Basha, traffic engineer, Summit Land Management

Always interesting commentary in your columns. Comparison to other cities in the United States is informative. What would be the best transportation system in a metropolitan area?

Definition of best is relative – very much dependent on each person’s perspective and experience.

Most freeways: likely Los Angeles. Least congestion: likely Gila Bend. Neither very desirable.

State with most roadway miles-per-square-mile: New Jersey. Fewest roadway miles per-square-mile: Alaska. Arizona ranks 8th lowest – though more roadways-per-square-mile than either Wyoming or Hawaii.

Metropolitan areas with most freeway lane-miles-per-person, in order: Kansas City, St. Louis, Houston, Cleveland.

Metropolitan areas with fewest freeway lane-miles-per-person, in order: Chicago, Tampa, Miami, New York, Portland, Sacramento, Phoenix.

Oh, freeway lane-mile means the number of lanes multiplied by the length. A six-lane freeway that is two miles long would be twelve lane-miles. A four-lane freeway that is three miles long would also be twelve lane-miles.

None of those mildly interesting statistics are particularly meaningful in determining the best transportation system.

The question of mobility versus accessibility is meaningful.

Mobility is the ability to move or be moved freely and easily.

Accessibility is the quality of being able to be reached.

The distinction for transportation systems is critical. Mobility means simply easy travel. Accessibility means easy travel from one desired place to another desired place.

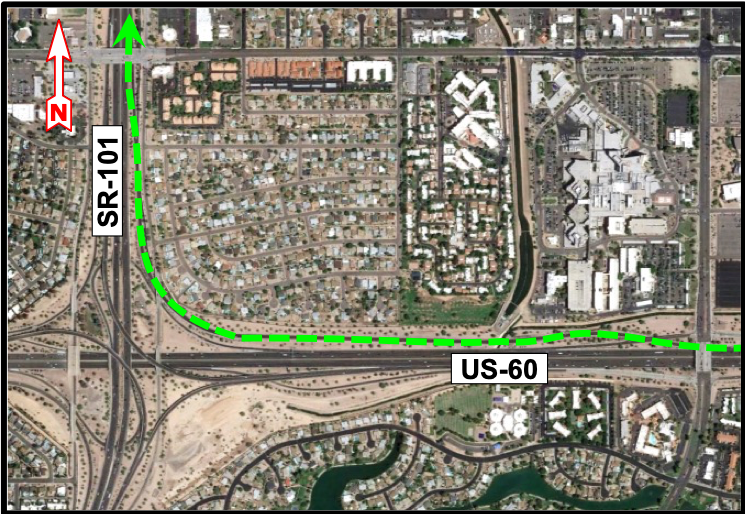

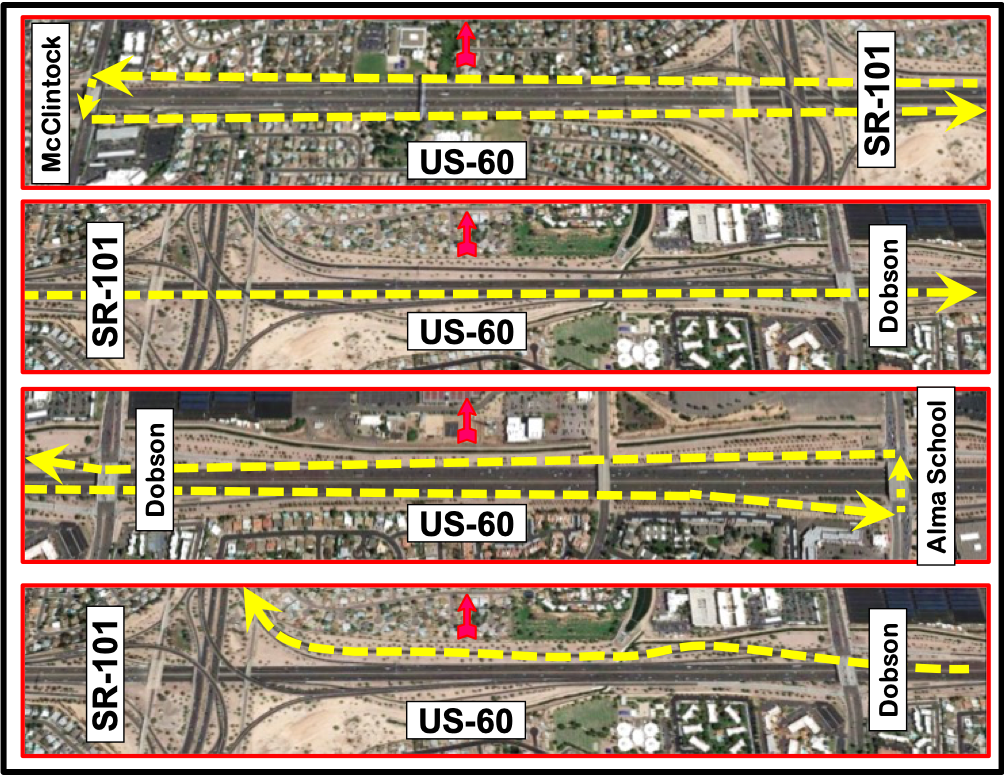

Anybody who has missed a freeway-to-freeway interchange knows the difference between mobility and accessibility. One such time-consuming error is westbound US-60 to northbound SR-101. Driving this ramp correctly is 1.4 miles. At a reasonable 50 to 60 miles-per-hour the travel time is 1.7 to 1.4 minutes.

Miss that ramp . . . it becomes 7.8 miles, plus two u-turns requiring left-turns at four stoplights! Assuming an average speed of 40 to 50 miles-per-hour, plus two-minute wait for each left-turn. that is 19.7 to 17.4 minutes. Yep, cannot get from the eastbound McClintock Drive on-ramp to the exit ramp to northbound SR-101. And it gets even longer when you have to stop for flowers or wine because you’re so late for dinner. (Not that anyone I know has had that experience.)

Mobility without accessibility exists in other forms. Longest distance between freeway exits in the United States? Nope, not in Puerto Rico. Florida Route 91 has one 49-mile stretch and one 40-mile stretch. Utah I-80 has the third longest at 37 miles. California I-40 has a 28-mile distance between Kelso and Ludlow, wherever they are. Arizona I-8, east of Yuma, has a 21-mile segment. Plenty of mobility on all those freeway segments, you’re moving the entire time, though you cannot leave the freeway to see or do anything or be anywhere.

Didn’t Cat Stevens sing about that, “Well you roll on roads over fresh green grass for your lorry loads pumping petro gas. And you make them long and you make them turn. But they just go on and on and you can’t get off.” Oh, he recently re-recorded “Tea for the Tillerman”. Do not bother, he had it right in 1971.

So, driving only has value if you go from a place where you do not want to be at that moment to a place where you do want to be soon. How do we provide that for everyone always? Easy, I have my car. Got roads?

Choice is critical. Sometimes we prefer to drive fast on a freeway, accessible exclusively by high-speed ramps. Other times we choose or need to drive slow on an arterial with intersections. People are happiest when they can realistically choose either facility type, and preferably choose between different routes for either type, any time of any day. Depending on our origin and destination, if we choose to drive on a freeway, we typically must also drive on an arterial or two.

(Frustration many have had is driving on an arterial with a speed limit of 40 miles-per-hour, and someone drives past at 50 miles-per-hour, then when the same car gets on the freeway with a 65 miles-per-hour speed limit, they still drive at 50 miles-per-hour. For some people, simply way too challenging to get the little numbers on their speedometer to match the numbers on the black-on-white signs.) {So, who was the letter “e” lobbyist who convinced the dictionary writers to have consecutive e’s in that word? We certainly do not pronounce it as the long e sound in speed.} While we’re not on the topic, ever try to explain to a person learning English how and why to pronounce or spell the time unit of “minute”?

The choice of either freeways or arterials is dependent on congestion. Often during peak commute hours, with the evening commute worse than the morning commute, freeways are too congested to be a comfortable or realistic choice. Paraphrasing Yogi Berra, no one drives on freeways during rush hour, they’re too crowded.

Freeways in metropolitan areas often suffer from congestion because of other drivers entering or exiting the freeway. In the past, the south SR-202 did not have an interchange with Lindsay Road. Ah, two miles without disruption. That excellent idea recently changed – watch the congestion increase now that the San Tan Freeway has a Lindsay Road interchange. At least neither the north SR-202 or the US-60 have a Lindsay Road interchange.

Another one of those transportation balancing dilemmas: through traffic versus local traffic. A foundational tenet of transportation: what is perfect in some situations is much less than perfect in other situations.

The best urban freeway system would include two or more travel lanes per direction with very infrequent entrances and exits – preferably only every five to ten miles. The separation from frequent ramps could be barriers or elevation. Now we’re talking mobility when we need it and accessibility only when necessary. Of course, the entries and departures are problematic.

Seattle’s I-5 includes four one-way travel lanes in the median, without entrances and exits for approximately seven miles. The lanes are reversible – southbound into the city center in the morning and northbound out of the city center in the afternoon. Denver, Minneapolis, Chicago, Cleveland, Atlanta, Tampa, Fort Lauderdale, and approximately two dozen other major United States cities have similar reversible directional expressway lanes. However, most of these facilities have entrances and exits at less than five-mile intervals.

The concept exists in Phoenix with direct High Occupancy Vehicle lane connections at some interchanges. The southbound SR-101 to the south SR-202 eastbound and the SR-202 bypass of the US-51 interchange are two examples.

Frequent entrance and exit ramps create friction; which increases disturbance, congestion, and travel time; which reduces capacity. Often, we only need to drive through an area without vehicles needing access diminishing our mobility.

The future is troubling. Metropolitan Phoenix has approximately 4.5M people now and is estimated to have 6.9M in 2025. That’s a 53% increase. Will our arterial street and freeway capacities increase by 53% in five years? At carefully selected high-congestion freeway locations in metropolitan Phoenix, would very-limited-access freeway lanes for several miles be possible? Would they be sufficiently beneficial compared to their construction costs?

Seems that all the good spots for freeways and arterials are taken. Can we construct enough new freeways? The recently opened South Mountain Freeway cost approximately $81M per mile. Can we widen all the existing freeways enough? The current SR-101 widening from four lanes to five lanes per direction, between I-17 and Pima Road, is costing approximately $7M per directional lane-mile. Fine, that’s a 25% capacity increase for 13 miles. We currently have 1,800 freeway lane-miles in metropolitan Phoenix. Will we have sufficient funds to increase those 1,800 freeway lane-miles by 53%?

In highly desirable metropolitan areas, intersections with stop signs eventually need traffic signals. Streets with traffic signals eventually need freeways. Historically in the United States, the prevailing perspective has been if one or two freeways are good, then many freeways are much better.

One of the unfortunate realities of freeways and freeway widening is that people will drive extra to use all the increased capacity and more. So post-construction, the congestion remains. In many respects, in spite of the continued congestion, that increased mobility is desirable. However, does anybody think travel in Los Angeles is appealing? Short of Elon Musk’s ultra-high-speed-tunnel, does an evolutionary higher capacity transportation system exist?

Cars dominate transportation in the United States. Eventually finances constrain our ability to accommodate our insatiable desire to drive. The best metropolitan transportation system would also include non-car systems. Rail and bus systems are necessary.

Light rail lines are analogous to freeways. Buses are analogous to arterials and local streets. A well-functioning ubiquitous arterial network is necessary to ensure the freeways perform well. Just as freeways without connecting streets are useless.; light rail lines require frequent, convenient, and comfortable bus connections. Some argue that buses are better than rail because buses can be relocated to fit changing needs, while rail lines cannot be relocated. Well, freeways are rather permanent, eh?

The Light Rail system initial cost in Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa was approximately $85M per mile. With a light rail system, once the very expensive track is in place, capacity can be increased by adding trains. When the metropolitan Phoenix Light Rail system first opened in January 2009, it operated at 10-minute intervals, because of covid, it now operates at 15-minute intervals. 5-minute intervals would be a 100% capacity increase over the initial 10-minute intervals. Purchase price for a light rail vehicle is approximately $7M total, not per mile.

Daily human migration patterns are astonishingly consistent. Freeways are a great invention for responding to the human desire for frequent travel. A few freeways in a metropolitan area serve us well. Too many freeways, like too many beers, are damaging.

Light rail lines respond well to the predictability of human travel.

Toronto, Ontario, Canada is widely regarded as the best city for transportation in North America. It has a freeway system that does not dominate the metropolitan area. The arterial street system is a well-developed grid system that complements the freeways. The light rail system consists of several routes that serve all geographic areas of the metropolitan area. Additionally, Toronto has an extensive system of highly compatible bus routes that complement the light rail system.

Best transportation system? Choices.

Curious about something traffic? Call or e-mail Paul at (480) 505-3931 and pbasha@summitlandmgmt.com.