Visitors take photos at Mather Point in the Grand Canyon in this 2019 file photo. More than 6 million people a year visit the Grand Canyon, pumping $1.2 billion into the region’s economy, another reason the park should be protected by a mining ban, backers of the proposal say./ File photo by Chloe Jones/Cronkite News

By Haleigh Kochanski | Cronkite News

WASHINGTON – The House voted Friday to permanently ban new mining claims on more than 1 million acres around Grand Canyon National Park, with supporters calling protection of the landmark canyon a “moral issue.”

The bill would make permanent a current mining moratorium that is scheduled to run through 2032. Supporters said a permanent ban is needed because the Grand Canyon is too valuable to risk possible damage from future mining.

“Protecting our environment is not a matter of choice or political preference,” said Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, in a statement from his office Friday. “It’s the only path forward for our country and our way of life.”

Grijalva, the lead sponsor of the canyon bill, said earlier this month that “the Grand Canyon should be the least controversial” place on the planet to consider protecting from mining.

But critics said that by limiting access to rich uranium fields around the canyon, the bill would have not only an economic cost but a cost to national security as well.

“Decreasing our reliance on foreign nations for critical minerals is an important part of ensuring our national security,” said Rep. Debbie Lesko, R-Peoria, in a statement released by her office. “The Grand Canyon region is home to uranium which is essential to many industries. We should not limit our domestic production of this important resource.”

That argument did not appear to sway House members, who voted 227-200 to approve the bill.

House members rejected a pair of amendments from Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Prescott, one that would have delayed the mining ban until a study was done to see if the area contained other valuable mineral resources, and another that would have exempted land in his district from the ban.

The House also approved two amendments, from Rep. Tom O’Halleran, D-Sedona, making slight boundary adjustments at the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument and the Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument.

The canyon mining ban was one of eight land preservation bills that were rolled together into the “Protecting America’s Wilderness and Public Lands Act.” The bill identifies nearly 3 million acres in four states – Arizona, California, Colorado and Washington – that would get new protections.

The Grand Canyon has been protected since 2012, when then-Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar issued a 20-year moratorium on new mining claims. The moratorium did not affect permits for existing mines in the region, which includes 1 million acres outside the park boundaries but still within the Grand Canyon watershed.

Supporters of the bill fear that new uranium mining in the region would contaminate the Grand Canyon or seeps and natural water springs in the area, in part because of the unusual geology of the region.

“Because of this highly complex, highly fractured geology in the region to the north and to the south of the Grand Canyon… the idea of mining uranium is really risky,” said Amber Reimondo, energy director for the Grand Canyon Trust. “You’re cutting through a lot of … layers and a lot of aquifers.”

That threat is particularly concerning to members of the Havasupai tribe, whose tribal home is in the canyon.

“The Havasupai Tribe has opposed a nearby uranium mine, the Pinyon Plain Mine (formerly Canyon Mine), for years,” Havasupai Tribal Chairwoman Evangeline Kissoon said in a prepared statement released by Grijalva’s office.

“The contamination from the mine has caused millions of gallons of precious water to be rendered unusable and wasted, and the mine has potential to contaminate the Redwall-Muav aquifer,” her statement said.

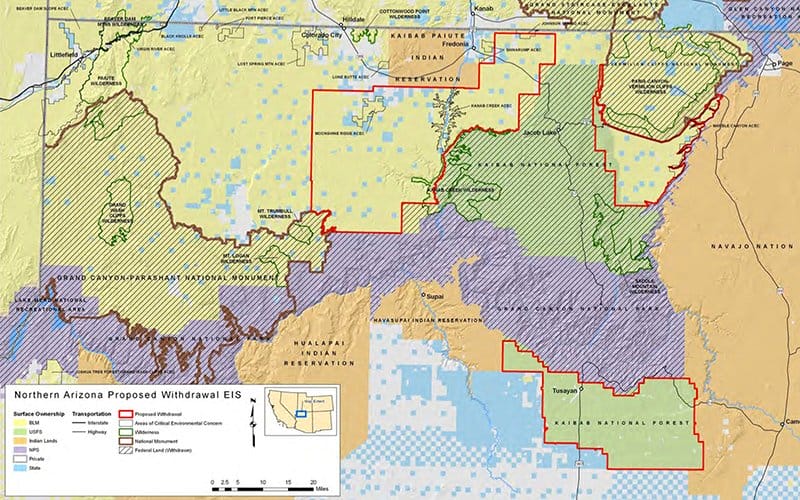

The Interior Department in 2012 imposed a 20-year ban on new mining claims on more than 1 million acres, outlined in red on the map, near the Grand Canyon. The House has passed a bill to make the ban permanent in those areas. (Map courtesy Department of the Interior)

Sandy Bahr, director of the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon Chapter, said legislation was needed because bureaucrats can only “withdraw” land – make if off-limits to activities like mining – for a maximum of 20 years, as Salazar did.

“Withdrawing it means that there can be no new mining claims,” Bahr said. “This area has been temporarily withdrawn, temporarily protected from uranium mining. but this (bill) will take that temporary protection and make it permanent.”

The bill now goes to the Senate, where its fate is unclear. Bahr said a canyon mining ban has died in the Senate twice before. But she noted that there is now a slim Democratic majority in the Senate, where Arizona Sens. Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly this week introduced a bill that would prohibit mining once a study is done on the national uranium stockpile.

“I’ve seen the Grand Canyon’s beauty from space and up close. It is a treasure for Arizona and for our country,” Kelly said in a statement on the Senate bill. “We can and must protect the unique public lands that our economy and communities depend on.”

The senators, like many supporters of the move, cited not just the environmental aspects of protection but the economic, noting that 6 million people visit the Grand Canyon a year, pumping $1.2 into the region’s economy.

President Joe Biden has indicated he will sign the House bill if it reached his desk. Bahr is hopeful.

“Hopefully we will be celebrating its passage in the House and in the Senate,” she said. “And I’ll know that something that is one of our national treasures is better protected,”

She said if the legislation fails to become law and the area’s groundwater isn’t protected, “the lives and livelihoods of many will remain in the balance.”