With an increasing number of days exceeding triple digit temperatures in Phoenix, a CDC report reveals that Arizona residents seeking refuge from the dangerous heat may face barriers to accessing cooling centers . /Photo by Nicole Neri | AZCIR

BY: SHAENA MONTANARI/Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting

Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting Arizona residents seeking refuge from extreme heat may face barriers to accessing cooling centers designed to shield vulnerable populations from dangerous temperatures, a new report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows.

Heat exposure and heat-related illness are on the rise and the age group most at risk for hospitalization—those 65 and older—may be unaware that cooling centers exist, or experience challenges accessing them because of a lack of transportation.

“Arizona is a national leader in both monitoring and responding to health impacts of heat, and is absolutely at the forefront of heat exposure in the United States,” said Evan Mallen, the report’s lead author, who is a fellow in the CDC’s Division of Environmental Health Science and Practice. The state, he said, “was a natural place to look first when it comes to both analyzing the challenges that Arizona has faced, but also the great work that Arizona is doing.”

The CDC analysis, which focused on Maricopa and Yuma counties, also reveals that the jump in heat-related inpatient hospitalizations is affecting populations younger than 65. A separate heat-associated death report from Maricopa County shows the majority of those who died outdoors from heat-related causes were under 65, and often unsheltered, suggesting there are a number of groups at risk of exposure to extreme heat.

The findings concern experts who say heat-related illness and deaths are preventable problems. With an increase in deaths attributed to people outside, including those experiencing homelessness, experts said access to indoor, air-conditioned cooling centers during periods of extreme heat is that much more pressing.

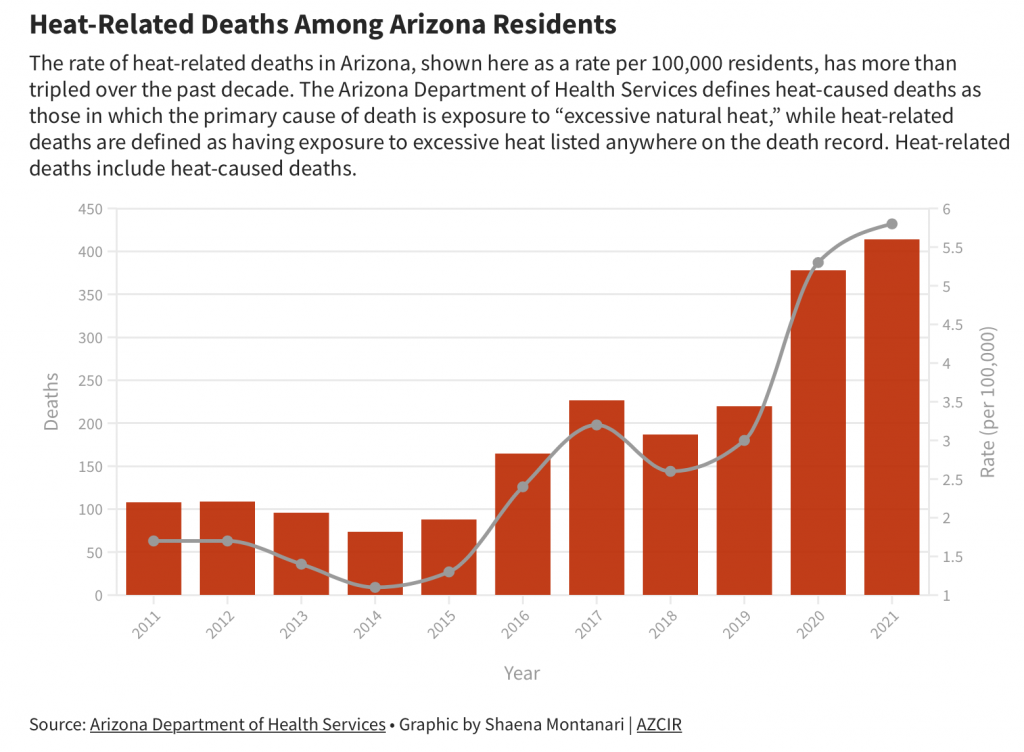

The rate of deaths related to heat in Arizona has more than tripled over the past decade. In 2021, 414 Arizona residents died from a heat-caused or heat-related illness. When counting non-Arizona residents, the death toll jumped to 552.

Arizona Department of Health Services data shows there were also 2,873 heat-related visits to emergency departments across the state in 2021, and 920 inpatient hospitalizations.

Climate data shows the start of triple digit temperatures in Phoenix has shifted earlier at a rate of one day every four years. Temperatures hit at least 100 degrees, on average, 114 days per year in the Phoenix area and 117 days per year around Yuma. In 2020, that number was 145 days in Phoenix and 148 days in Yuma, both new records.

“Extreme heat is a threat multiplier,” said Melissa Guardaro, assistant research professor in the Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation at Arizona State University. “So, if you have an unhoused issue, this is really a problem during extreme heat periods.”

Guardaro, who wasn’t part of the CDC study, co-authored a report that showed the number of cooling centers in Maricopa County alone declined from 106 to 19 at the onset of the pandemic in 2020, representing a more than 80% reduction in the number of available facilities. Some cities and towns, such as Queen Creek and Fountain Hills, were left with no cooling centers during the height of the pandemic.

The CDC report notes that in 2019 and 2020, about half of the cooling centers in Maricopa County were in an area with “high social vulnerability,” or geographic areas with characteristics such as a high poverty or limited access to transportation. In Yuma County, the majority of cooling centers were in areas considered vulnerable.

Identifying and locating cooling center locations is difficult because no coordination exists at the state level. Instead, sites are organized by local governments, faith-based groups and other nonprofits.

AZCIR searched county health websites and called public health officials in all 15 counties in an attempt to create a statewide database of cooling center locations. AZCIR identified 169 cooling centers across Arizona, although as of the publishing of this article, not all counties had responded.

Maricopa County has the largest number of cooling centers, which are mapped by the Maricopa Association of Governments and known as the Heat Relief Network.

The patchwork of cooling center operations and management has led to significant differences in available locations and hours from one county to another.

In Bullhead City in Mohave County, for example, cooling centers with extended hours are only activated once the temperature reaches 120 degrees. Heat-related deaths in the county have quadrupled over the past several years, from 14 in 2016 to 60 in 2021, according to data from the Arizona Department of Health Services.

State and county data shows that heat-related deaths are not only rising outside major metro areas, the demographics of those most at risk are also shifting.

In Maricopa County, where the bulk of heat deaths in the state occurs, the majority of people who died from heat-associated causes indoors were 65 or older, while the majority of those who died outdoors were younger, according to a recent report from the county.

A decade ago, 54% of heat-associated deaths in Maricopa County were indoors. In 2021, indoor deaths had decreased to 25%.

Most heat deaths in the county now happen outside, including more than 300 people experiencing homelessness who died in 2020 and 2021. The data also shows a strong correlation between outdoor heat related deaths and substance abuse.

In addition to analyzing 10 years worth of inpatient hospitalization data, the CDC surveyed 39 adults over 65 in Yuma County about cooling centers and heat-related illness. The researchers found 44% of respondents had experienced “heat-related medical symptoms” in the last year and 64% did not know where a cooling center was located.

In 2014, Maricopa County Department of Public Health evaluated cooling center use by surveying those who use them. But “a key limitation was that participants surveyed were those who had the awareness and means to travel to and spend time at a cooling center,” MCDPH spokesperson Sonia Singh said in an emailed statement.

In 2023, MCDPH will try to fill those survey gaps and evaluate cooling centers to better understand how to reduce barriers to use, Singh said.

Arene Rushdan, an organizer for cooling centers run by the Arizona Faith Network in Maricopa County, said she knows unhoused people who use their cooling centers are often concerned about their personal belongings getting thrown away or stolen if they go inside.

Cooling centers may also be difficult to reach without transportation, and the hours are limited: “People aren’t just hot from nine to five when most businesses are open,” Guardaro said. Minimum temperatures in the summer in Phoenix sometimes don’t dip below 90 degrees.

Rushdan said longer hours and weekend cooling center openings are critical. But to stay open longer hours, she said, more funding would be needed for staff positions rather than relying on volunteers.

The CDC report suggests that increased public health communication about cooling centers, increased hours and more convenient locations could help improve access.

Mallen said behavioral changes, such as staying out of the sun during the hottest parts of the day, and infrastructure improvements, such as shade structures and trees, are also critical for protecting people against extreme heat.

“There should be more of a comprehensive response,” he said.

AZCIR’s Emma Brocato contributed reporting to this article.

This article first appeared on Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.