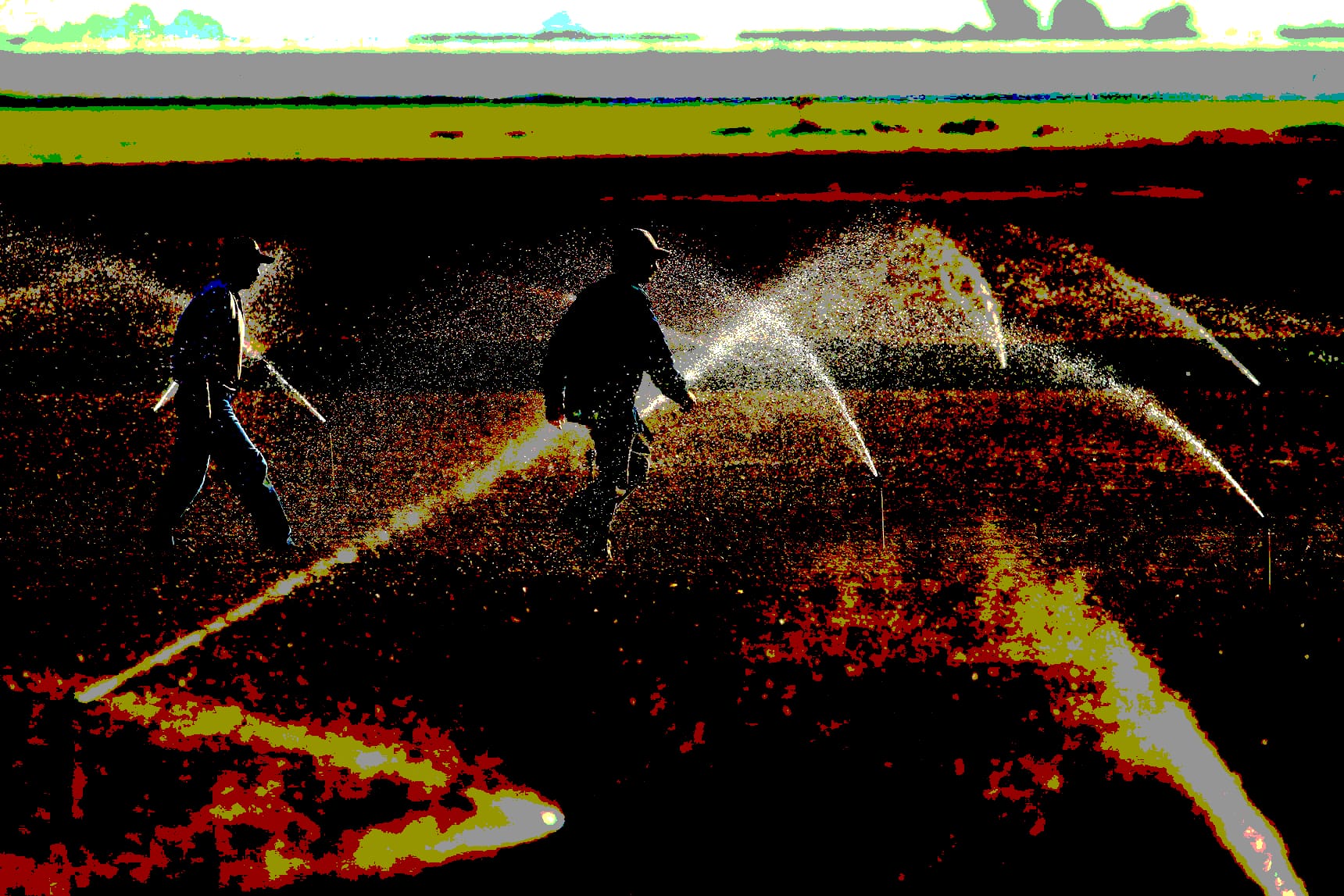

Workers inspect an irrigation system on a broccoli farm in Imperial Valley, California, in October 2011. || Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

The river waters a lot of our food. What happens as it dries up?

By Benji Jones|| Vox

It’s a classic Italian-American meal: a crispy Caesar salad with a plate of marinara pasta.

You can find it in restaurants across the country, but depending on the time of year, many of the ingredients come from just one region. Yuma, Arizona, along with California’s Imperial Valley, produces more than 90 percent of the country’s winter leafy greens and much of its vegetables. Arizona is also a major grower of wheat, which the state exports to Italy for making pasta.

Historically, this made a lot of sense. The region has nutritious soil and a warm climate for growing food year-round, even when the rest of the country is frozen over.

There’s just one problem: The water that farmers use to grow these crops comes from the Colorado River, and the Colorado River is drying up.

The iconic river is in its 23rd year of drought, according to the Bureau of Reclamation, and the two largest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, have sunk to historic lows, prompting a series of water restrictions. Under climate change, the drought could worsen in the years ahead.

That means residents in the West might have less water for lawns and long showers, but it’s a much bigger problem for agriculture because farmers use about three-quarters of all the water that people take from the river. Some farmers have already had to restrict their water supply, and there are much steeper cuts to come.

Which brings us to this slightly depressing point: When farmers use less water, they tend to produce less food. And that could cause food prices to go up, even more than they already have. Winter veggies, like lettuce and broccoli, could take a big hit, as could Arizona’s delectable wheat. More concerning still is that the shrinking Colorado River is just one of many climate-related disasters that are threatening the supply and affordability of food.

Historic water cuts are already hitting farmers

Meandering 1,450 miles from northern Colorado to the Gulf of California, the Colorado River is the lifeblood of the American West. It provides water to nearly 40 million people across seven states, Mexico, and more than two dozen tribes, and it irrigates millions of acres of land.

The river is governed by a complex set of policies — collectively known as the Law of the River — that dictate how much water each state or tribe receives, and which will lose water first when the government imposes restrictions. (Typically, groups that have been using the water for longer have higher-priority water rights, including Indigenous tribes.)

Last August, the federal government declared a water shortage on the river for the first time, in response to projections that Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, would be at just 34 percent of its capacity by the end of 2020. The declaration, known as a Tier 1 shortage, triggered cuts that affected Central Arizona, which has low-priority rights.

Farmers in Pinal County, Arizona, who grow alfalfa, wheat, and other crops, suffered the most, said Paul Brierley, a former farmer who now leads the Yuma Center of Excellence for Desert Agriculture at the University of Arizona. “They’ve had to fallow [stop planting] about 40 percent of their acreage because they lost all their Colorado River water,” he said.