Flag of the. Colorado River Indian Tribes

The 1922 Colorado River Compact virtually ignored tribal communities, but amid drought, Indigenous leaders have gained a say in what happens next.

By Debra Utacia Krol | The Arizona Republic

Tribal leaders stood proudly in front of a row of flags from the 10 Indigenous communities whose lands converge with the Colorado River.

They spoke about their status as equal players in the future of the Colorado and the role they will play in the high-stakes negotiations to set new management protocols for the river that more than 40 million people depend upon for their lives and livelihoods.

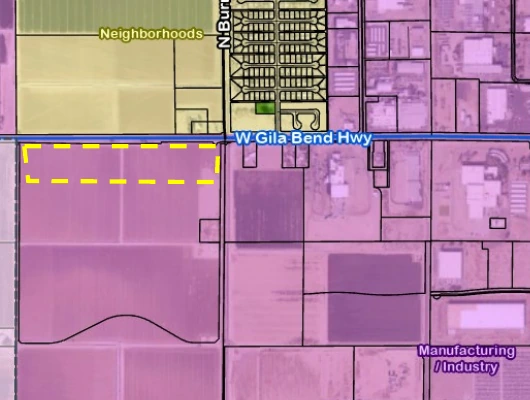

Sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with regional water managers and a high-ranking Interior Department official, Amelia Flores, chairwoman of Colorado River Indian Tribes, and Stephen Roe Lewis, governor of the Gila River Indian Community, signed an agreement to contribute about 500,000 acre-feet of their own water to an effort to keep Lake Mead levels high enough to prevent another round of mandatory cuts.

They were part of tribal delegations from throughout the Colorado River Basin gathered in Las Vegas in December 2021 during the annual meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association. Tribal officials were included in panels and discussions throughout the conference, where previously they had been relegated to their own panels.

This new willingness to work with tribal governments as equal partners in stewarding water diverges from more than 100 years of history, when tribes’ rightful claims as senior water rights holders were dismissed despite pivotal court rulings, legislation and federal policies.

“Historically, tribes have not been a part of the negotiations around the management of the Colorado River,” said Maria Dadgar, executive director of the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, during a panel discussion. “But let’s say this is history, because that is no longer the case.”

Tribes played a critical role in the implementation of the Drought Contingency Plan, which was crafted in 2019 after the current river management guidelines fell short in addressing severe drought conditions in the basin.

“We are going to see that tribes are here to play an integral role in all of the Colorado River management decisions,” said Dadgar, a member of the Piscataway Tribe in southern Maryland. “We should look at tribes and think of tribes as key stakeholders.”