(Disclosure: Rose Law Group represents Emmerson Holdings.)

By Chase Emmerson | Bloomberg

Despite the drop in housing starts, it is getting more and more expensive to develop raw land into the finished lots that homebuilders need. Rising land and land development prices are contributing to housing supply and affordability challenges, yet this issue is not getting much attention outside of those in the industry.

Much has been made of vertical construction costs (things like lumber, siding, and windows) decreasing because of supply chains normalizing after COVID, and the drop in housing starts as a result of mortgage rates spiking in 2022. However, horizontal development costs (things like roads, sidewalks, and sewer lines) have continued to rise. When looking at why horizontal development costs have continued to march higher despite the slump in housing starts, the elephant in the room is U.S. federal government spending.

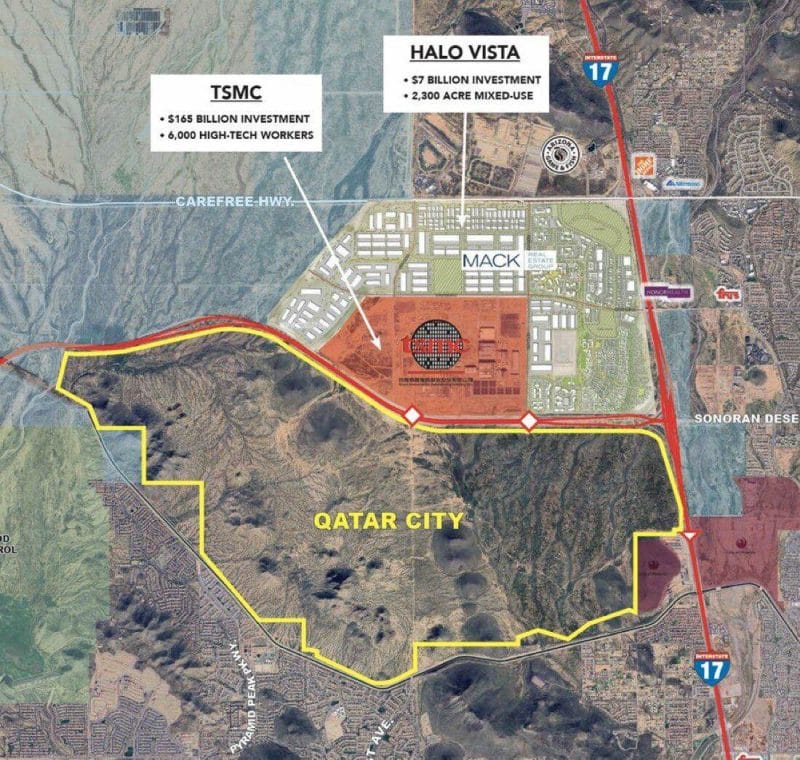

Last year, we were in the middle of developing a master-planned community called Storyrock in Scottsdale, Arizona. It seemed that practically all the labor, equipment, and concrete in the market was being sent out to build the new $40B Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) fab in nearby Phoenix. If labor or materials for horizontal development were not being sent to TSMC, then it seemed they were going to Intel’s new fabs or the Interstate 17 highway improvement project.

In late 2022 and 2023, many in the industry had hoped that horizontal improvement costs would drop or at least flatline. After all, in metro Phoenix, single-family housing permits had dropped by nearly 30% between 2021 and 2023 due to rapidly rising mortgage rates and the hit that had on affordability and buyer demand. Unfortunately, there was no such relief in Phoenix or in many other major metros that benefited from the CHIPS Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), and other federal spending. Additionally, due to the impact of this federal spending on materials prices, the impact was felt broadly across the country.

Major aggregates suppliers, which provide the raw materials used to construct new roads, noted that, despite weak demand in the residential market, their overall demand remained mostly steady. A leading U.S. aggregates supplier, Vulcan Materials, stated that demand growth for public projects has offset softness in private projects, particularly residential. Between steady demand for their products and constrained capacity, prices for aggregates have continued to rise since 2022.

Vulcan Materials reported that aggregate prices are up 29% from Q3 2022 to Q3 2024. This is not just being felt in the aggregates space. Grading contractors have also noted the same theme: weakness in demand for new residential projects being offset by strong demand for public projects, employment/manufacturing and clean energy projects. This trend is set to continue. As of the latest U.S. Department of Transportation reporting, just more than 1/3 of IIJA funds have been spent.

So as horizontal improvement costs have continued to rise, let’s now turn to what has been happening with raw land and finished lot prices. The value of land is typically seen as a residual, with the price of the raw land equal to the finished lot value less the horizontal improvement costs needed to “finish” the lots (plus some margin). All else equal, as the horizontal improvement costs rise, the value of the land should decrease. However, as John Burns, CEO of John Burns Real Estate Consulting and top adviser to large U.S. homebuilders noted, “the biggest shortage in the country is the entitled land we build on.”

This shortage of entitled land, most of which is closely held by highly capitalized landowners, has led to an unusual situation where land prices and improvement prices were both rising even as new housing starts dropped. Seeing the shortage of entitled land, many landowners have held firm or even raised prices. Most large landowners today own their land free and clear, since foreclosures, debt restructurings, and bankruptcies cleared the land market of almost all debt following the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

Since the GFC, banks have been wary to lend on land, and landowners have been equally wary to employ debt. This lack of debt enables large landowners to simply wait for improvement costs to come down or for finished lot prices to increase until they get the price they want for their land.

Improvement costs have not been coming down, so finished lot prices have adjusted higher for land to transact with homebuilders. Even though homebuyer demand today is not what it was in 2021, large homebuilders are competing to find more finished lots to fill their pipeline. And in the process, they are pushing finished lot prices higher.

The ongoing rise in horizontal development costs, exacerbated by significant federal spending on public projects, poses a challenge for the housing market. While the decline in housing starts might suggest a temporary relief, the persistent demand for materials and labor, driven by large-scale infrastructure initiatives and CHIPS Act-supported investments, continues to push horizontal improvement costs higher. Landowners, for their part, are holding raw land prices firm due to the shortage of entitled land, their lack of debt, and the favorable medium and long-term outlook for housing demand.

Taken together, this has led to increased prices for both land and finished lots, further complicating affordability for homebuyers, and is putting strain on homebuilders’ margins. While the federal government has promoted infrastructure investment and industrial policy through the IIJA and the CHIPS Act, it is important for policymakers and those in the housing industry to recognize how these priorities intersect with another policy goal: increasing the supply of affordable housing.