By Megan Myscofski |Arizona Public Media

SULPHUR SPRINGS VALLEY – Cities and agricultural operations across the West put intense pressure on groundwater supplies. In some rural regions, few rules govern how, when and how much water can be pumped.

That’s true in rural southern Arizona, where wells are drying up as cities grow, large farms move in and the megadrought continues. In Cochise County, some residents are pushing the state to better manage dwindling groundwater supplies, although not everyone is on board.

Near her home, Tara Morrow can walk inside a crack in the ground that’s deeper than she is tall.

“There’s a really good snake den back in there,” she said.

The fissure even swallowed part of the road near her home. When these deep cracks open up, she said, they make even a quick grocery run tough.

“You know, the desert is a beautiful place, and it’s also a very harsh place,” Morrow said.

It’s already dry in Sulphur Springs Valley, and it’s getting drier. The aquifer that lies many feet beneath the surface used to be much higher, but as water is pumped and not replaced, the aquifer drops and the ground above it becomes unstable.

Morrow and her neighbors are seeing the water wells they use for their basic needs – cooking, cleaning and showering – dry up as large farming operations move in and have to drill deeper for groundwater.

“It is a little bit scary to think that one day you’re going to wake up and your place might be condemned,” Morrow said.

Groundwater management isn’t just an Arizona problem. Colorado’s legislature just voted last month to put $60 million toward groundwater sustainability. California and Nevada also struggle with the issue.

In certain rural pockets of Arizona, some residents are pushing for stricter rules on pumping. Those who are fed up with dropping groundwater levels want the two basins in this valley to become Active Management Areas, or AMAs.

Kathleen Ferris researches water policy at Arizona State University, and she knows all about AMAs – she helped get the policy on the books in 1980. The state regulates groundwater use in five AMAs considered heavily reliant on mined groundwater, but no such restrictions exist in 80% of Arizona.

“The advantage to being in the AMA depends on who you’re talking to,” Ferris said. “But for one thing, it means that you can’t drill a well, and pump as much groundwater as you want, without constraint.”

Anyone who’s already pumping water before an AMA is established would get grandfathered groundwater rights. Someone wanting to drill a new well would have to prove someone else’s supply would not be harmed.

The Phoenix, Tucson, Casa Grande and Prescott areas tightly regulate groundwater under existing AMAs, as does the Santa Cruz Valley west of Sulphur Springs Valley. The option to create a new one was built into the 1980 Groundwater Management Act, but no one has tried to do it until now.

“We found a statute that was right there waiting for us,” said Rebekah Wilce, co-founder of Arizona Water Defenders, which has been gathering signatures to get a proposed AMA on the ballot this November for parts of Sulphur Springs Valley.

They’re on track to do it.

‘A mini-Grand Canyon’: Desert opens up as aquifers decline in Cochise County

By Megan Myscofski |Arizona Public Media

SULPHUR SPRINGS VALLEY – Cities and agricultural operations across the West put intense pressure on groundwater supplies. In some rural regions, few rules govern how, when and how much water can be pumped.

That’s true in rural southern Arizona, where wells are drying up as cities grow, large farms move in and the megadrought continues. In Cochise County, some residents are pushing the state to better manage dwindling groundwater supplies, although not everyone is on board.

Near her home, Tara Morrow can walk inside a crack in the ground that’s deeper than she is tall.

“There’s a really good snake den back in there,” she said.

The fissure even swallowed part of the road near her home. When these deep cracks open up, she said, they make even a quick grocery run tough.

“You know, the desert is a beautiful place, and it’s also a very harsh place,” Morrow said.

It’s already dry in Sulphur Springs Valley, and it’s getting drier. The aquifer that lies many feet beneath the surface used to be much higher, but as water is pumped and not replaced, the aquifer drops and the ground above it becomes unstable.

Morrow and her neighbors are seeing the water wells they use for their basic needs – cooking, cleaning and showering – dry up as large farming operations move in and have to drill deeper for groundwater.

“It is a little bit scary to think that one day you’re going to wake up and your place might be condemned,” Morrow said.

Groundwater management isn’t just an Arizona problem. Colorado’s legislature just voted last month to put $60 million toward groundwater sustainability. California and Nevada also struggle with the issue.

In certain rural pockets of Arizona, some residents are pushing for stricter rules on pumping. Those who are fed up with dropping groundwater levels want the two basins in this valley to become Active Management Areas, or AMAs.

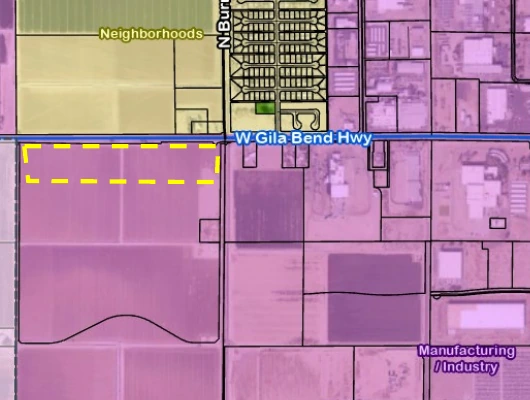

Fissures are appearing more often in the Douglas and Willcox basins of Cochise County as the aquifers beneath them continue to shrink. When they open up, Tara Morrow says, even a quick run to the store is difficult. Photo by Megan Myscofski/Arizona Public Media

Kathleen Ferris researches water policy at Arizona State University, and she knows all about AMAs – she helped get the policy on the books in 1980. The state regulates groundwater use in five AMAs considered heavily reliant on mined groundwater, but no such restrictions exist in 80% of Arizona.

“The advantage to being in the AMA depends on who you’re talking to,” Ferris said. “But for one thing, it means that you can’t drill a well, and pump as much groundwater as you want, without constraint.”

Anyone who’s already pumping water before an AMA is established would get grandfathered groundwater rights. Someone wanting to drill a new well would have to prove someone else’s supply would not be harmed.

The Phoenix, Tucson, Casa Grande and Prescott areas tightly regulate groundwater under existing AMAs, as does the Santa Cruz Valley west of Sulphur Springs Valley. The option to create a new one was built into the 1980 Groundwater Management Act, but no one has tried to do it until now.

“We found a statute that was right there waiting for us,” said Rebekah Wilce, co-founder of Arizona Water Defenders, which has been gathering signatures to get a proposed AMA on the ballot this November for parts of Sulphur Springs Valley.

They’re on track to do it.

“It might not be the perfect solution,” Wilce said. “In fact, it probably won’t be, but it is the only thing, seemingly, that we actually can do and that we can do ourselves at the ballot.”

Not everyone supports their efforts, however. Riverview, a Minnesota dairy company, moved in in recent years and built one of the largest operations in the area. A spokesperson declined an interview for this story but said the company is neutral on the ballot measure.

Sonia Gasho, president of the Cochise County Farm Bureau, called the AMA designation extreme. The bureau, she said, prefers smaller-scale regulations.

“Our policy as Farm Bureau is that we want to respect private property rights,” Gasho said. “We want to conserve water. And we want to do that in a way that is as little government oversight as possible.”

This is a familiar tension in the West, where decades-old laws protecting privately held water rights butt up against the realities of a warming, drying and growing region.

Morrow said the fissures opening up near her home threaten her ability to live in the Sulphur Springs Valley long-term.

“It really looks like a little mini-Grand Canyon, doesn’t it?” she said, marveling at the crack.

Morrow said action needs to happen soon, before her well dries up completely.

“I love agriculture. I grew up in an agriculture community, a big part of my life is agriculture,” she said.

But, she also said, if farms keep expanding unchecked, the region will become uninhabitable for those who’ve lived here for years.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by Arizona Public Media, distributed by KUNC, and supported by the Walton Family Foundation.

“It might not be the perfect solution,” Wilce said. “In fact, it probably won’t be, but it is the only thing, seemingly, that we actually can do and that we can do ourselves at the ballot.”

Not everyone supports their efforts, however. Riverview, a Minnesota dairy company, moved in in recent years and built one of the largest operations in the area. A spokesperson declined an interview for this story but said the company is neutral on the ballot measure.

Sonia Gasho, president of the Cochise County Farm Bureau, called the AMA designation extreme. The bureau, she said, prefers smaller-scale regulations.

“Our policy as Farm Bureau is that we want to respect private property rights,” Gasho said. “We want to conserve water. And we want to do that in a way that is as little government oversight as possible.”

This is a familiar tension in the West, where decades-old laws protecting privately held water rights butt up against the realities of a warming, drying and growing region.

Morrow said the fissures opening up near her home threaten her ability to live in the Sulphur Springs Valley long-term.

“It really looks like a little mini-Grand Canyon, doesn’t it?” she said, marveling at the crack.

Morrow said action needs to happen soon, before her well dries up completely.

“I love agriculture. I grew up in an agriculture community, a big part of my life is agriculture,” she said.

But, she also said, if farms keep expanding unchecked, the region will become uninhabitable for those who’ve lived here for years.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by Arizona Public Media, distributed by KUNC, and supported by the Walton Family Foundation.