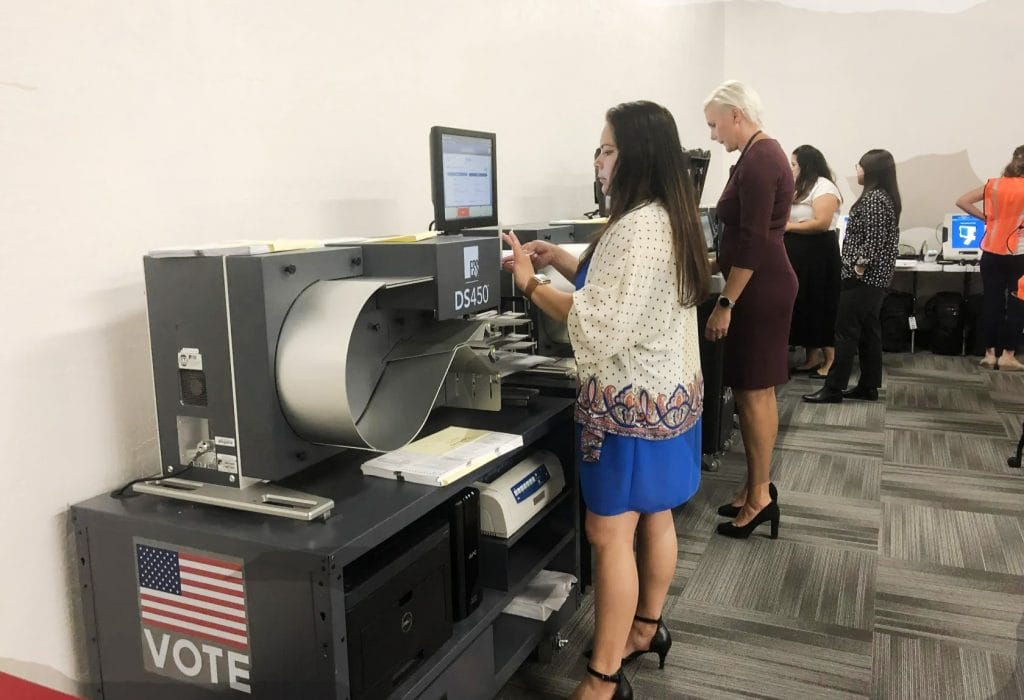

Kori Lorick, election director for the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office, explains the logic and accuracy testing process to three local party observers at a Yuma County elections building on June 30. /Photo by Rachel Leingang / Votebeat

By Rachel Leingang | Votebeat

A state-owned eight-seater airplane touched down in Yuma County on the last day of June to deliver a team from the Arizona secretary of state’s office to a nondescript building on Main Street for a crucial test — one they hoped could help rebuild public confidence in elections.

The secretary’s staff wore orange vests to distinguish them from others in the room. Legally required observers for the local Democrats, Republicans, and Libertarians wore lanyards in colors associated with their parties. A table stacked with waters and sweet treats sat near the stars of the show: the county’s voting machines and tabulators.

The logic and accuracy tests, required by state law, must be successfully completed before any Arizona voter can cast their ballot and before counties can count any votes. They serve to confirm that all voting machines work properly and meet every state requirement, no matter how arcane. They test whether each counting machine accurately tallies a predetermined, marked set of ballots.

The tests are relatively obscure. But election machines featured prominently in all kinds of conspiracy theories after the 2020 election. These tests are public officials’ chance to combat that, but in order to convince a skeptical public, election officials must first get the skeptical public to show up. Despite widespread wariness and unfounded accusations that voting machines could be used to cheat, few people come to watch the lengthy, intensive tests that the machines undergo.

Photo by Rachel Leingang /Votebeat

Aside from the required party observers and county and state staff, only two members of the public — one a reporter and one a lawyer for the Democratic Party — were in the audience for the early morning test in Yuma.

If members of the public had come to observe, they would have seen just how thorough these tests are, and the minute details they’re checking.

Like the color of text displayed on a ballot machine, a small snag in Yuma’s test.

The screen on an accessible voting machine displayed the candidates’ political parties in black text. Per the state’s Elections Procedures Manual, the text color should have corresponded to the printed ballots — red for Republicans, blue for Democrats, and yellow for Libertarians.

The state testers, on their tiny airplane, would need to come back to Yuma.