By Anthony Marroquin | Cronkite News

By Anthony Marroquin | Cronkite News

Marv Freeman had lost interest in almost everything. He was constantly exhausted, dehydrated, and had begun to lose some of his balance.

The doctors told him he just had a cold, or the flu. His wife knew something else was at play. And so they kept visiting more doctors, until he finally got a proper diagnosis.

Freeman had valley fever.

“I didn’t really have a life,” said Freeman, 81. “It took about five months of my wife’s tender love and care to be able to function properly.”

Freeman’s story is not too uncommon in Arizona. It’s been 13 years and he now helps run Arizona Victims of Valley Fever Inc., to create awareness about the disease and help others like him on their way to recovery.

Of all the valley fever cases reported nationwide, approximately 65 percent of those are in Arizona. The hardest hit areas are the Maricopa, Pima and Pinal counties.

The fungal spores that cause the disease are sensitive to changes in weather. An increase in rain could cause the spores to grow more readily, while a decrease causes them to spread easier through dust.

But according to the Arizona Department of Health Services, there still isn’t enough research to determine a correlation between the amount of spores in the ground, and the number of cases reported this year.

That’s why this year’s El Niño is stirring interest among experts studying the disease.

The weather phenomenon is predicted to bring above average rainfall to the state this year.

In 2011, Arizona reported 16,472 cases; the most since 1997 when ADHS started requiring all positive tests to be reported. During the next three years, the numbers dropped back down to about 5,700 a year, but started to rise again in 2015, with over 7,600 cases reported.

“There is a big interest in whether [El Nino] will have an effect on growth… but there is no way of telling how it will affect [it],” Shane Brady, an epidemiologist with ADHS, said.

Brady said factors like increased clinician awareness, and changes in testing could cause the numbers to fluctuate. He said the department would have to wait until next year to make any assessments on how El Niño affects the spread of the disease.

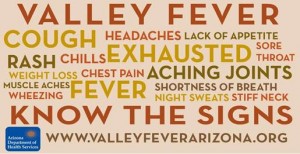

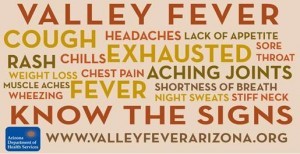

For now, ADHS recommends people take precautions and ask their doctor to test them for valley fever if they feel exhausted, or have a fever or cough.

The disease is spread by breathing in the spores carried by blowing dust. Staying out of dust and seeking shelter during dust storms can lower the chances of contracting valley fever.

The disease attacks the lungs and can sicken people for months. Only 40 percent of those who are infected will see any symptoms, but in five percent of the cases valley fever can cause severe pneumonia.

In about one percent of the cases, the fungus can disseminate and reach the brain.

“You don’t have the same quality of life, it’s that simple,” Freeman said. “It’s imperative for people now to come to grips with the disease.”