By Kianna Gardner | Cronkite News

ongtime Bisbee resident Renee Reed remembers how the dilapidated home across the street used to look.

“It was really cute and quaint, but over the years I’ve had to sit here and watch it just disintegrate,” Reed said.Nearly three decades ago, the home was so beautiful an artist asked Reed if he could sit on her front lawn and paint a picture of it. The picture of that bright green house, with its delicate yellow and red accents, hangs on her wall.Today, with the roof caved in, paint chipping away and lawn unkempt, the home’s charm has vanished. It’s one of dozens in the city that has sat vacant for decades – many in the middle of the city’s tourism hub – and faces the possibility of being demolished.

Bisbee resident Renee Reed holds up a painting of the house across the street that is now considered dilapidated. /Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite NewsCity officials said owners who owe back taxes abandoned some of the houses, while other owners have fallen on hard times and can’t afford to remodel homes that have been in their families for generations.

Some residents view the dilapidated homes as vital pieces of Bisbee’s history and fear the gentrification that could come with rebuilding. Others believe they are eyesores harming the tourism industry, attract squatters and threaten people’s safety.

“It’s always been a tightrope because we’re not here to destroy generational homes,” said Andy Haratyk, public works director. “It’s taken a long time to get to a point where we can even have conversations with people about this without them getting emotional.”

Estimates of the number of vacant and dilapidated houses in 2017 are hard to come by. Some locals claim there are hundreds, but city officials say the number of homes that require immediate attention is closer to 60. Many public records were lost earlier this year when the city hall caught fire, according to the city clerk.

Nearly 30 percent of the 3,500 homes in Bisbee were vacant in 2015, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The bulk of houses are nestled in Old Bisbee, the tourism focus of the former mining town that was carved into the mountains in the late 1800s. The community has won awards as a historic tourism draw.

And it’s been lucrative. Bed-tax revenue increased nearly $40,000 from 2015 to 2017, said Jennifer Luria, the visitor’s center supervisor.

Joel Ward, a building and zoning inspector in Bisbee, is a longtime resident who believes the issue of dilapidated homes is nearing resolution. /Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite News

Officials anticipate tourism will continue to climb, but Haratyk and Joel Ward, Bisbee’s building and zoning inspector, are worried the dilapidated homes may detract from the city’s antique ambiance.

“There’s a point where we look at it and there’s nothing left to salvage,” Ward said of some of the homes. “We don’t want to save junk, and we should be ashamed we let these houses even get like this.”

Some of the homes are perched on the side of hills, ready to topple over on homes below them. Others are occupied by squatters, who sometimes start fires for warmth, turning the buildings into hazards for the closely quartered Bisbee neighborhoods, said Bisbee fire chief George Castillo.

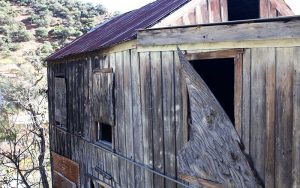

Some of the dilapidated homes in Bisbee have been boarded up and are occupied off and on by squatters. Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite News

“We have concerns about the placement of these abandoned buildings,” Castillo said. “Some are up on hills and if they catch fire, it would be difficult to get a fire truck to them.”

Much of Bisbee was built on hillsides and can only be accessed by staircases or very narrow winding roads. The fire department incorporated hose back packs so firefighters can run up the stairs and lay water lines to fight fires, Castillo said.

Earlier this year, a house fire consumed at least six other nearby structures. The cause of the fire is unknown, but the hillside terrain on which the blaze occurred made fighting the fire difficult. The event led the fire department to search for possible routes to the most dangerous structures, Castillo said.

Some believe only homes in imminent danger of collapsing should be considered for demolition.

Long time Bisbee resident Mike Anderson moved to the city for its uniqueness and history. /Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite News

“Each one of these buildings has fascinating stories to tell not because of the building itself, but because of the people that lived there,” said Mike Anderson, a retiree and Bisbee resident. “Tearing down dilapidated buildings is demolishing history.”

Anderson believes if the buildings are torn down, property taxes will rise, triggering gentrification in the eclectic city. Anderson moved to Bisbee more than 30 years ago for its quirkiness and rich history, qualities he says may be lost should the homes be torn down and rebuilt.

“If property taxes go up because your neighborhood becomes gentrified, those people can no longer afford to live there,” Anderson said. “That’s the downside of renovation. When you put money into something, it raises the cost.”

Before a home or building is either torn down or remodeled, plans for the property must be presented to the design and review board. The board begins by analyzing whether or not a building is “historically significant” to Bisbee.

Currently, if a property is deemed significant, it can’t be demolished. Any exterior renovations in a remodel must be in sync with the historical appearance of the rest of the city.

Some of the upgrades are out of the price range for many Bisbee residents, said Tom Slusser, co-founder of the Bisbee Housing Association, a nonprofit that remodels dilapidated homes in Bisbee.

“If we want to keep the historical presence in the city, this is just something we have to do,” Slusser said. “It’s not just about having the knowledge and skills to remodel the homes. You have to have a lot of cash for these old homes.”

Tom Slusser recently purchased a dilapidated property he plans to remodel into multiple smaller and affordable homes. /Photo by Kianna Gardner/Cronkite News

Slusser and his wife, Nanette, have remodeled a handful of homes in Bisbee that others had considered teardowns. Each home takes nine months to a year to renovate and the construction normally begins with replacing the plumbing and electrical systems, Slusser said.

Slusser said he has yet to see a home he couldn’t remodel. He believes he could fix some of the 60 homes city officials list as dilapidated.

“We take the worst of the worst,” Slusser said. “It’s in the eye of the beholder and people like us may see a potential remodel.”

Haratyk said it may take time for people to warm up to restoring homes.

“Someone won’t pay $250 (thousand) or $300,000 for a new home and live next to a shack with people squatting in it,” Haratyk said. “That’s part of the paradigm shift that’s happening in Bisbee.”

Balancing the thoughts and opinions of Bisbee locals and officials is a major challenge for city officials. Ward said a few decades ago, the problem was much worse and the city was riddled with hundreds of homes that have been either been demolished or remodeled.

He said the primary focus now is working things out with home owners who refuse to address the problem.

“The city is more of a ‘back to the 70s’ city,” Slusser said. “Everyone wants to get along, they don’t want to be the bad guy.”

FIVE of Arizona’s newly elected public officials visit Rose Law Group

Dozens of constituents gathered this morning in the Scottsdale office of Rose Law Group to hear from: Maricopa County Supervisors Mark Stewart, Thomas Galvin, Kate