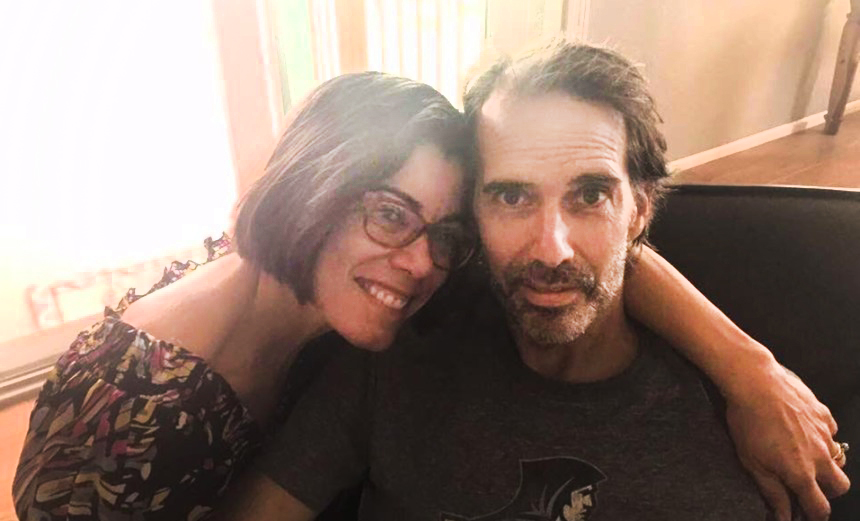

It took me a long time to find a new home for the belongings he left behind

By Fernanda Santos | The New York Times

Ms. Santos, a former national correspondent for The Times, teaches journalism at Arizona State University.

My husband and I shared a narrow, shoebox-shaped closet in our home here, his clothes facing mine from double-hanging wardrobes mounted on the walls. After he died of pancreatic cancer on Nov. 1, 2017, a month after his diagnosis, I’d often wander into the closet to search for his smell on his shirts. My mother caught me one day sniffing his shirts and crying, and said, “You can’t keep doing this forever.”

“What should I do?” I asked.

“You need to find the right people to give his clothes to,” she replied.

I packed his shirts, slacks, shoes, belts and ties into the gunpowder-gray suitcases we’d bought for our trip through western Ireland years earlier. That same day, a Federal District Court judge in San Francisco ordered the Trump administration to keep on renewing the permits that gave young undocumented immigrants permission to temporarily live and work in the United States, as prescribed by the Obama-era program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA.

I noted the events in my journal in short, unemotional sentences: “Cleaned closet, packed Mike’s stuff away;” “Good news of the day: DACA still alive.”

Sign Up for Debatable

Agree to disagree, or disagree better? We’ll help you understand the sharpest arguments on the most pressing issues of the week, from new and familiar voices.

I parked the suitcases in a corner of my garage, where they stayed for 16 months, gathering dust as the president made a mess out of the country’s already messy immigration system.

In these months, my daughter’s nanny, a naturalized citizen, lost her brother in Mexico, where he had been deported last year after living illegally for 26 years in Phoenix. (His wife and three children still live here.) The nanny said that he’d died of a broken heart.

Also in these months, accounts of Central Americans released from immigration detention and dumped at the Greyhound bus station in town began showing up in my news feeds, followed by reports about Central Americans lost in the punishing desert that straddles the Arizona-Mexico border, or about children falling ill and dying in overcrowded Border Patrol stations.